Imagine the Art Ensemble Of Chicago jamming with Duke Ellington and the Willem Breuker Collective, injecting their jam with elements from the New Orleans funk, blues and brass band music, and you’ll get a pretty good picture of what this CD by this Dutch trombone player sounds like.

GROOVEMASTER

Who knew we’d been missing something this good?

Kevin Whitehead, Chicago 2002 – liner notes

Liner notes & reviews

Chris Abelen is stubborn, does things his own way. That much is plain from his quirkly quintet CD’s for BVHAAST, DANCE OF THE PENGUINS and WHAT A ROMANCE. This, his third disc, is his most conceptually rich and ambitious, yet it was recorded years before the others, almost a decade before he considered releasing it. How the CD came to be: Abelen had been thinking about starting a little big band, after putting in his years with respected Dutch units like Willem van Manen’s Contraband, J. C. Tans and the Rockets and the Willem Breuker Kollektief. Mulling over the possibilities, Chris went back to listen to this program which, as he tells it anyway, went down like the spikes on a pineapple when folks heard it live. But when he listened again, he changed his mind about starting that new band. No point: he’d done it right the first time.

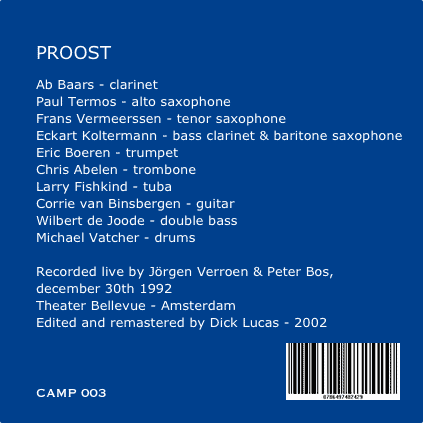

What he had done right – when commissioned, in 1992, to write a set for Breuker’s year-end Klap op de Vuurpijl festival – was to assemble a tentet which cut across generational and stylistic lines, from free players to a fusion picker to a tubist who’s played everything from pizza-parlor dixieland to improvised theater gigs. Then Chris devised a series of Ellington-style concertos to showcase his crew, whom he knew from here and there: Baars and Boeren frrom the Rockets, Germany’s Koltermann from Contraband, van Binsbergen from some of her projects, Termos from when Chris’d subbed in Paul’s tentet. Like most Amsterdam musicians he’d crossed paths with Vatcher, de Joode and Fishkind around town.

Abelen didn’t apportion solo space to showcase everyone equally, nor to play favorites. He just wanted to make a lively, well-balanced set. As ever, he had some strong and contrary ideas in mind. He didn’t want to write for sections, in the usual brass vs. reeds big-band manner, and he wanted to avoid the pissing matches that ensue when players of the same horn sit side by side. So; there’s no sectional writing, and no redundant instrumentation. Instead, he groups the voices on a case by case basis, shifting the leads around.”i spent a lot of time on that. I composed the notes first, and lived with them awhile, and then decided how to divide them up.”

In big bands, the full orchestra typically drops out for the solos, accompanied only by the rhythm section. ”I didn’t want the musicians standing around looking at each other and waiting for the soloist to finish. I thought it must be possible to write backgrounds that let soloists play without limiting them too much.” In most bands, the other players lay out for drum of bass or air-bass spots, tempting the soloist to drop out of tempo, not always a good idea. But de Joode, Vatcher and Fishkind solo within the ensemble like everyone else.

With Duke’s concertos, you can usually ID the featured player quickly: Rex or Cootie will make an early entrance and hold center stage. Here, a minute or two may pass before the spotlight settles on somebody-and even then it may move onto someone else. (Two pieces are double concertos. Abelen sneaks in de Joode’s arco grind after Vermeersen’s veal-tender tenor on “Modder”; on “Mis” trombone bats cleanup for tuba.) in part he’s playing a game with the listener: can you spot the mole? Chris is not above planting false clues either: you’ll think he’s setting up Player A, and then B steps out. It may be germane that he studied at the Sweelinck Conservatory, where the similarly playful and contrary composer Misha Mengelberg teaches.

But the long buildups also serve to place the solos in context, to establish a mood more than recommend a course of action. “I didn’t give any specific instructions, and no one asked for any. Paul Termos, Ab Baars, Eric Boeren, Frans Vermeerssen-they’ re all such nice solo players, I specifically asked them because of the way they play. Like Ab-he has such an unromantic way of playing clarinet, and fits where a more romantic player wouldn’t. I could hear him in my head as I was writing this music.”

On “Scale” Boeren is the horse led to water: he pounces on the pogo-stick rhythmic scheme and makes it even jumpier, amplifying the composer’s idea even as he tops it. The piece effectively channels Eric’s excitable side, but he makes his improvisation sitespecific: you won’t find another solo like this one in his burgeoning discography.

Abelen likes to get push folks a little to one side of their normal thing too. Van Binsbergen loves snaky, Zappaesque electric solos; here she plays an amplifed steel-string classical guitar with a hard and spiky attack, as on her feature “Sem.” Her axe is often used as a horn or trembling mandolin, though she can also percolate with bass and drums in a refreshingly undemonstrative way. Like Wilbert she also plays in Chris’s quintet with Tobias Delius and Charles Huffstadt. “Corrie is the perfect guitarist for what I write-despite her typical reservations about it.”

This wasn’t the first time Vatcher and de Joode teamed up; they’d already been goosing Michiel Braam’s popping piano trio, for instance. They sound so good, it’s a wonder they aren’t paired more often. Wil and Michael push and pull at the time, can fade to nothing and then come roaring back, or lay in the pocket and groove down the middle. Vatcher in particular sounds terrific throughout: the loud eruptions, the delicate metallic details, the weird big gestures, the daredevil act he plays with the beat, all radiate his peculair charm. “ For this project, I wrote complete percussion parts, giving Micheal the freedom to use them or not. He seemed to use them a lot.”

The writing has its own charms; those backgrounds and foregrounds abound with beautiful, intricate textures. The hovering midrange chords and the searing trumpet eand clarinet near-unisons on “Mis” may recall Gil Evans, another master of fresh timbral combinations, but Abelen’s charts don’t resemble his any more than they do Duke’s. Dutch composer/ improvisers often betray a fondness for Stravinksky; I’d never noticed it before with this one, but the clockwork rhythms on ‘Bus,” “Mis,” “Sem” and elsewhere suggest the connection. (Igor’s “Ebony Concerto” for Woody herman makes an instructive comparison.)

Those aren’t the only springy pieces here; the leader clearly wanted to get everyone’s juices going. Termos got so carried away on “Proost,” which draws out his deconstruced-cool-school beste, that he sailed past his end cue. “He didn’t want to finish, so we played some of the backgrounds again: there are actually two backing parts there, one cued by Ab, one by me. This repetition created some doubt about where we should stop.” As you’ll hear, that problem took care of itself.

One nice surprise is that the self-effacing Abelen takes an uncharacteristically long solo on “Mis,” showing off the brash Ruddy sound and swaggering time usually kept under wraps. And check out the subtle changes in the landscape passing behind him, as swingtime slowly comes unglued and re-glued.

So why did this knockout set fail to floor ‘em at the Bellevue Theater back in ’92? “I don’t know. I had a 10-piece band like Willem Breuker, and I’d played with Willem, and it was his festival, so maybe people were expecting something else. And we played sitting down, close together on the big stage, so we could synchronize. We also took long pauses between pieces, to prepare. Almost like it was chamber music.” The Klap festival is a bit of a year-end blowout, and folks may not’ve been in the mood for sit-down music, however sparky. I wasn’t there, but it’s also possible that the self-effacing boss exaggerates a bit for effect. (On tape, the audience response doesn’t sound so limp.) no matter; it’s a good story, and it does let Chris off the hook for making us wait this long to hear this suff. Who knew we’d been missing something this good?

Kevin Whitehead, Chicago 2002

GROOVEMASTER

January 2005 PROOST

Imagine the Art Ensemble Of Chicago jamming with Duke Ellington and the Willem Breuker Collective, injecting their jam with elements from the New Orleans funk, blues and brass band music, and you’ll get a pretty good picture of what this CD by this Dutch trombone player sounds like.

On this CD he is accompanied by some great musicians like Eric Boeren on trumpet, Larry Fishkind on the tuba and Corrie van Binsbergen on guitar.

The result is a very tight free jazz big band in which all members have all freedom to perform their solos over the on-going basic melodies.

The songs all come from live recordings from 1992, during the Klap Of The Vuurpijl festival but they don’t sound dated at all.

“Modder” sounds like a weird New Orleans street parade band. The song has a stumbling rhythm in which the stubborn horns have all freedom. Plenty of soulful sax solos here. The song keeps its lazy New Orleans funk feel, despite the stubborn character of the song.

“Bus” is a speedy brass band track with plenty of squeaking and battling horns.

“Proost” sounds like a drunk big band, swaying all over the place. Plenty of screaming sax solos over a bopping backing.

“Sem” has some staccato clockwork rhythms and a biting funky guitar solo.

The songs goes from festive to very atmospheric.

“Bob In China” is a Chinese free jazz melody with some beautiful horns.

This CD offers the creme de la creme of Dutch adventurous free jazz.

Jazz Weekly

There’s something — and hope it isn’t economics — which finds so many outstanding performances by improvisers from the Netherlands, organized around “little” big bands. Sure, smaller and larger combinations turn out memorable work, but when exceptional Dutch improv first comes to mind so do Misha Mengelberg’s ICP Orchestra, Willem Breuker Kollektief’s and, more recently Michael Braam’s Bik Bent Braam and the ensembles led by Martin Fondse.

Since so many of these bands are the vision of one person, writing and arranging for 10 to 12 players allows room for Holland’s idiosyncratic soloists, with just enough musical heft on tap to move the sessions past blowing sessions or free-for-all improvisations.We know of these particular groups because most of them have existed in one form or another for many years, yet other players have dabbled in that formula as well. Proost is the result of that dabbling; a record of a one-off, 10-piece group put together on the second last day of 1992 by trombonist Chris Abelen. Abelen, who has since made his reputation with a quintet, has sat on tapes of this, in-retrospect, all-star session fore more than a decade. The lukewarm audience reception at the time made him undervalue the performance.

Indeed, it does have its weaknesses. But since his newfound faith in the program that spurred its release means that the trombonist will probably never organize a group like it again, it’s tantalizing to hear how a set of first-class players interprets the eight tunes. Written for Breuker’s year-end Klap op de Vuurpijl festival, the tentet members include big (modern) band veterans like Abelen, as well as types whose first allegiance is to repertory jazz, Klezmer, fusion or free music.

“Bus,” for instance, has the sort of jaunty, semi-classical lilt that you would expect from the ICP or maybe Globe Unity, complete with slowly syncopating ticking clock rhythms from drummer Michael Vatcher, a long-time associate of ICP reedist Michael Moore. Yet it’s another ICP stalwart, clarinetist Ab Baars, who is featured here. Working in a quiet neo-bop mode, he echoes 1950s New York mainstay Tony Scott. Until some split reed dissonance and intentional squeaks are introduced, Baars sticks to the coloratura range, as his bent notes are framed by a horn choir.

These 1950s echoes seem genuine, for Abelen’s writing on the title track sounds like it could have come from some of the advanced composer/arrangers of that time like Teddy Charles, Gil Evans or George Russell. Here, though, the alto line which seems to slide between acrid no-compromise swing and honeyed movement, isn’t played by Phil Woods or Gigi Gryce, but Paul Termos, who has experience in bands led by Mengelberg and bassist Maarten Altena. He starts with sharp freebop trills that morph into overblowing and shrill claxon calls. Bomb dropping and cymbal pinging, Vatcher stays with him every step of the way, but referencing the same era. So does the straightforward foursquare work of Wibert de Joode, one of the country’s most accomplished bass masters. The bassist whose experience encompasses bands led by Abelen, Baars, Braam as well Yank avant-gardists like saxophonist Charles Gayle links the rhythm of the 1950s with the virtuosity of the 1990s.

Not to be outdone, fusion rears its head on frisky “Sem,” in the person of guitarist Corrie van Binsbergen. Someone who since the mid 1980s has worked in pop contexts as well as doing jazz gigs with Abelen, she starts off playing near acoustically, eventually rocking out, adopting stout Johnson Brothers-style guitar licks to the attendant music. Other horns provide the backing riffs, but her chief spur in all this is the tuba of Larry Fishkind, usually found in klezmer settings.

That same back-to-the-future mixture also sets up “Mis,” the CD’s longest track as well as Abelen’s feature for himself. Here though, while Fishkind’s sepulchral tuba line rumbles through the brass basement, the trombonist’s 1930s-style plunger showcase takes place among rim shots from the drummer and countermotifs from the reeds. Ending open-horned as he ascends the scale and references a ‘bone sound a few decades more contemporary, the backing he has written for himself reflects sophisticated progressivism.

Proost isn’t without its faults however. “Bob in China” (sic), the final piece is rife with faux Orientalisms, including a gong sounded at the top and in the coda bookending a theme that is more vaudeville Chinese than a legitimate Sino-sound. Furthermore, a few too many of the other pieces appear to merely end with the soloist or band suddenly stopping, as if ideas had been exhausted, instead of those concepts being followed to a logical

conclusion.

Still, even if the CD isn’t at the highest rank it will appeal to those who can’t get enough of mid-sized EuroImprov bands and those interested in hearing trombonist Abelen in a different context.

Track Listing: 1. Modder; 2. Bus; 3. Mis; 4. Scale; 5. MF-2Hd; 6. Proost; 7. Sem; 8. Bob in China

Ken Waxman

De Volkskrant

The trombonist Chris Abelen is usually quite happy in a subordinate role, for instance in Willem van Manen’s Contraband or the Breuker Collective. When appearing as a leader, however, he does so with deliberation, getting right to the heart of the matter, such as in the case of the two quintet CDs on which, just like his employers, he has twentieth-century music sung at a jazz party. His capacity for self-criticism is apparently highly developed, and it must have expanded even further when in 1992 he gave the concert recorded here. The audience’s response was lukewarm, doubts arose in the mind of the maker, and the recordings were shelved. Fortunately Abelen changed his mind, because with ten musicians, his broadest palette so far, he puts his own stamp on chamber jazz, being as refined in construction as it is expressive. Four reed instruments, three brass, a guitar, bass and percussion provide a texture of constantly shifting colours in spicy, Stravinskian gyrations or impressionist pastels, and from those often bitter-sweet chords improvisations release themselves from a group of soloists. These don’t immediately rush into their own realm but remain true to the thematic material, partly because Abelen embeds their variations in accompaniment figures that provide just enough direction. A guitar instead of a piano and sober percussion from Michael Vatcher see to it that the touch remains light and airy; that said, this is music that keeps you on the edge of your seat.

Frank van Herk

Volkskrant 28 november 2002

Trombonist Chris Abelen is meestal tevreden met een dienende rol, bijvoorbeeld in Willem van Manens Contraband of het Breuker Kollektief. Als hij zich als leider manifesteert doet hij dat weloverwogen, en is het meteen raak ook, zoals op de twee kwintet-cd’s, waarop hij, net als zijn werkgevers, twintigste-eeuwse gecomponeerde muziek laat zingen op een jazzfeest.

Zijn gevoel voor zelfkritiek is kennelijk sterk ontwikkeld, en het moet zijn versterkt toen hij in 1992 het concert gaf dat op deze cd is vastgelegd. Het publiek reageerde lauw, de maker ging twijfelen, en de opnamen bleven op de plank liggen. Gelukkig heeft Abelen zich bedacht, want met tien musici, zijn breedste palet tot nu toe, speelt hij eigenzinnige kamerjazz, even verfijnd van constructie als expressief.

Vier rieten, drie koperblazers, gitaar, bas en slagwerk mengen op telkens andere manieren hun kleuren in pittige, Stravinsky-achtige raderwerkjes of impressionistische pastels, en uit die vaak friswrange samenklanken maken zich improvisaties los van een groepje solisten. Die hollen niet meteen hun eigen straatje in maar blijven trouw aan de thematische uitgangspunten, ook omdat Abelen hun variaties inbedt in begeleidingsfiguren waar net genoeg sturende invloed van uit gaat.

Een gitaar in plaats van een piano, en sober slagwerk van Michael Vatcher, zorgen ervoor dat de toets licht en luchtig blijft; toch is dit muziek voor op het puntje van de stoel.

Frank van Herk

Volkskrant 28-11-2002

Westzeit

Neun Musiker bringt Chris Abelen auf die Bühne des Amsterdamer Theater Bellevue und nennt das untertreibend ‘eine kleine Big Band”. Das war vor zehn Jahren. Erst jetzt kommt die CD dazu auf den Markt und man fragt sich, warum er solange damit gewartet hat. Abelen setzt auf mehrstimmige Bläserarrangements, um den gesamten Klangkörper auszuloten. Das führt dazu, dass sich die acht Titel zu einer imaginären Suite erweitern. Atmosphäre und rhytmische Struktur – eine Kombination, die bei Chris Abelen in guten Händen ist. In Eric Boeren fand er zudem einem Trompeter, dessen Schärfe für zusätzlichen Drive sorgt.

Klaus Hübner

WESTZEIT januari 2003

It was with nine other musicians that Chris Abelen appeared on the stage of Amsterdam’s Theater Bellevue, describing the group with a feeling for understatement as ‘a small big band’. That was ten years ago. Only now is he releasing the recording of that performance, which raises the question as to why he has waited so long. Abelen focuses on multi-voiced wind arrangements in order to do full justice to the group’s combined sound potential. The result is eight titles that make up an imaginary suite. Atmosphere and rhythmical structure are in good hands with Chris Abelen. In Eric Boeren he also has a trumpeter whose brilliance gives the whole added drive.

Klaus Hubner